I’m very thankful for this opportunity!

The Mooring Stone Volume 1

My new zine is now available to buy on my Big Cartel site.

This zine (really a newsprint broadsheet) is all about the Kensington Runestone, which was dug up in a field in western Minnesota in 1889. The runestone tells a fairly dubious story of vikings coming to Minnesota in the 1300’s, and I’ve been researching it and making work about it for the past year. You can read The Mooring Stone from multiple angles, with competing narratives tracing the edges of the newsprint like the runes on the stone itself. Meant to be puzzled over and turned around, this document braids together stories of runestone copycats, portraits from the prairie, salvaged accounts of the runestone's creation, and staged photographic reenactments into a web of unreliable details. $10 shipped.

Newsletter

Good Country People

I’m selling a few copies of my zine “Good Country People”. It has 20 photos in it, all about small town museums, roadside mysticism, and the “rural gothic”. The title comes from a story by Flannery O’Connor where a boy pretends to be a bible salesman and steals a girl’s wooden leg. “I’ve gotten a lot of interesting things this way,” he says before running off across the onion field.

Second edition of 24 copies. Printed on newsprint. $20 shipped.

Photos from Germany

Two years ago I lived in Karlsruhe, Germany, for a summer, making sculptures at the Kunstakademie Karlsruhe with Klasse John Bock. Here’s a few photos from that time, in no particular order.

The Disappearance of Maurice Graves

I have a few copies of a new zine for sale up in the ol big cartel. Go check it out!

“The Old West End” is back in stock!

Order it here: http://www.niknerburn.bigcartel.com

All books are shipped directly from me. I usually make shipments on Wednesdays and Fridays. Once you order, you might have to wait a few days for it to ship, but you’ll get a notice in your email once it does. As always, email me with any questions about your order!

There is also a few at Zenith Bookstore in West Duluth. So if you’re in Duluth, support our local bookstore!

"The Old West End" re-print

“The Old West End” may have sold out, but never fear - the reprint is on the way. Count on it sometime in the next month. In the meantime, enjoy a selection of some photos from the book at Perfect Duluth Day.

The Old West End

Books are finally shipping! Buy it here: https://niknerburn.bigcartel.com

EDIT: The first run of books has sold out. I’ll post updates on a second print run soon.

Some new artwork from school

Yes, I’m back in school, teaching and learning remotely during my second semester in the University of Minnesota’s MFA program. Here's a look at some of the recent work I've been making.

This installation has three overhead projectors; on one wall is projected a photograph of a cave and a brushfire. On the opposite wall, the third overhead projector illuminates a moving 25 foot long transparency scroll containing photographs I've taken, images from my family's archives, and photographs from the Hennepin County Library's collection. The scroll follows a loose narrative, sequencing images of young boys playing with dollhouses, dollhouse interiors displayed at the Minnesota State Fair, demonstrations of various crimes by the Minneapolis Police for public education, caves along the Mississippi river, interiors of immigrant settlement houses, and men with hidden faces. The scroll is turned at the viewer's own pace, as a self-guided tour in which any number of illuminated montages and sequences can be made. The scroll ends with images from the demolition of Minneapolis' Gateway District, when this now-vanished neighborhood in downtown Minneapolis was bulldozed as part of a plan to displace the many unattached men who lived in Washington avenue’s many single room occupancy hotels. The “redevelopment” ultimately destroyed nearly 40% of downtown Minneapolis.

At the back of the room, I've installed a backlit dollhouse with transparent photographs installed in the windows, which have had their dollhouse glass replaced with fresnel lenses. Fresnel lenses are typically used for magnifying light in large-format view cameras and lighthouses. However, the magnification only works at specific angles - turn your head or pull your eyes too far back, and the backlit image disappears.

The images in the windows are photographs of men's bedrooms in the old Washington Ave hotels, taken right before the Gateway's redevelopment in the 1960’s. The city government had a variety of photographers document the properties of the neighborhood to help create the political will to demolish the unsanitary buildings. In the photographs of bedrooms, the personal effects of the anonymous men who lived there are arranged like still lifes, with pin-up calendars, dirty socks, and empty bottles scattered around.

Some of the men who lived in the Gateway had never married, but many had families that they had left behind. Some of these men ended up in the Gateway because it was in the biggest railroad town between Spokane and Chicago. Others hadn't come from far at all - I read a story of a man who had abandoned his own family in south Minneapolis, then spent the rest of his life drinking in a hotel room by the river, only a few miles away.

This project is partly based on the story of my great-grandfather, Joseph Nerburn, who vanished from the family's North Minneapolis boarding house in 1930. His wife, Eva Brown Nerburn, died mysteriously that same year. Their 6 children grew up as orphans, living at different orphanages across the Twin Cities. The oldest child, Lloyd, eventually became my paternal grandfather (my dad's dad). Joseph's disappearance, and possible involvement in the death of his wife Eva, are enduring mysteries in my family.

Skipping stones in the driftless

In the fall of 2019, I visited the Crystal Creek Citizen Artist Residency for a week. I wrote this piece as part of the program’s reflection series, and Erin Dorbin also published it on their website. I’d encourage you to read all of the other artist reflections on the Crystal Creek website, also. This is a great residency program for anybody who wants support to pursue their open-ended community work in a really special place.

Above: my makeshift portrait studio on the side of the road in Houston county. I spent most of my residency making roadside portraits for folks in Houston county, setting up in a different county gathering place each day. I hooked my printer up to a deep-cycle marine battery and made prints on the spot for subjects to take home. Sometimes it worked, other times it didn’t; but the emphasis was on the conversations and serendipitous encounters that start to happen when word gets out that an itinerant photographer is printing portraits in the ditch.

In Gore Vidal’s novel, Duluth, he describes a town that bears only a passing and poetic resemblance to Duluth, Minnesota where I live. Vidal's Duluth is situated on the edge of a desert, not Lake Superior. Native flamingos wander amongst Spanish moss that hangs from the trees lining the city's grand boulevards. Simultaneously, the same Duluth landscape in the novel is covered by snow drifts and streets slicked with black ice that send cars skidding. Clearly, his Duluth is a psychedelic sister-city to the real place, with a jumbled mirror image that clearly isn’t meant to line up. Sometimes, the history of Vidal’s deranged Duluth does mirror actual events from the city in northern Minnesota, but it’s hard to tell where the history ends and the myth-making begins.

To top it off, Vidal also includes a few layered narratives; characters in Duluth will die and reappear in a popular television soap opera which characters in the book watch weekly. In one scene, a real estate agent from Duluth (the book) dies after crashing into a snow drift, only to reappear in a courtroom scene in Duluth (the TV program). She pauses the courtroom drama to speak to a bewildered former client of hers through the television, recommending a few new properties that just came on the market. At a certain point, you stop asking which narrative you’re in, and dipping between them becomes a cryptic pleasure. It suggests a parallel world, just on the other side of ours, similar but different, which you can sometimes pass back and forth between without knowing. Reading it was good preparation for spending time in the Driftless.

Mike’s dolls, Spring Grove, Minnesota. “Gotta do something with that high ceiling.”

The word driftless refers to glacial drift; when glaciers pass through a region, they often leave boulders and other debris on the landscape in their wake. Geologists call this drift; since the glaciers that shaped much of Minnesota's geography mysteriously skipped this region of the upper Mississippi, they left behind no glacial drift, hence the name driftless. Why the glaciers skipped this part, nobody knows for sure. Everything that has happened here since then owes a little bit to that early enigma.

Erin Dorbin, my host during the residency week, said that she felt like Houston County had a secret hiding around every hill. As we drove around, from historic societies to obscure roadside monuments to lovingly preserved little prairie churches, I began to sense the same thing. From atop a grassy bluff, looking around with her, I could physically see across the 569 square miles of Houston county, but if I squinted, I felt like I could be seeing the corresponding bluff country of Wisconsin, Iowa, or Illinois. Squinting harder, I could even see the fjords of Norway, the hollers of Appalachia, and the highlands of Laos.

Even the name of the place itself caused confusion with people back home. I had to clarify that I meant Houston, Minnesota, not Texas. The place is hard to describe--not because it lacks specificity, but because it embodies more specificities than I’m used to. It’s Houston County, sure, but it’s a lot of other places at the same time.

Above: Rushford, Minnesota’s grocery store deli, with portraits of Miss Rushford from over the years.

One day, I met and photographed a man named Wally operating a thrift store. He had two prosthetic legs. He had lost one leg to the bite of a brown recluse spider, and the other to diabetes. He moonlighted as a karaoke DJ, but he dreamed of becoming a motivational speaker. On that same day, I listened to another man hold forth on the roadside about the simple beauty of Andrew Wyeth‘s paintings. Later, a woman showed me how she could mimic the calls of every owl in North America.

Later still, I spent an evening in an underground house and listened to a couple reflect on escaping the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran. As the light faded from the valley, I stood in the county fairgrounds as a man I met at the library considered the “tension between a historic document and the story that we tell to describe it”. The landscape felt like the biggest library, and I was just brushing my fingers across the spines as I walked down the stacks. High crests and low lands, deep dives and surface tensions.

Wally.

I spent one day photographing in Choice, an unincorporated little place, tucked in a valley that’s fed by a creek. While setting up my makeshift photo studio on the roadside, I met Ilene, who’s lived in Choice for a long time. In this picture, she’s holding a stack of photocopied newspaper articles, all about Choice, that she brought out to show me. In the pile was a framed copy of the 1870 farm census, which showed her homestead as being occupied by a single man named Ole Richardson, as well as “3 horses, 4 milk cows, 10 other cattle, 20 sheep, and 9 swine”. That year, Ole’s farm produced “750 bushels of spring wheat, 400 bushels of Indian corn, 250 bushels of oats, 50 bushels of Irish potatoes, 225 pounds of butter, and 25 tons of hay”. You coulda’ done worse, Ole.

Behind Ilene is the Choice bluff, which used to be decorated with lights every Christmas. People would drive from all over to see. The old Norwegian lady who hung the lights, since passed, used to bake cookies and give away a jar of them to every person who came to see her display. Ilene drove her golf cart back to her house and brought me a small Tupperware of the same cookies. “I got the recipe from her, and she had gotten it from another old Norwegian lady who had gotten it from another,” she said to me. “So Choice goes way back. What else do you wanna know?”

Choice: a town

that has no stores, no post office, no internet searchable census results.

A sign at the bottom of a lush valley

A spot in Minnesota

where aster, bluestem

bergamot, blazing star,

bloom straight

to highway’s shoulder.

-Rachael Button, 2018 citizen artist in residence

A while back, Ilene told me, the little creek that flows through Choice flooded. It was the subject of much local press at the time, and she showed me the yellowed and brittle proof in her stack of papers. For a brief moment, I could hear the rumble of a distant flood, of conspiring waterways, of the ghosts of glaciers twisting their way down a mighty and mysterious road.

Ilene, in Choice.

Nicole Rupersburg's "Remaking a Jail in Rural America"

Nicole Rupersburg wrote a great piece about my collaboration with Calvin Phelps and the Pike School of Art in McComb, Mississippi. I think she really hit the tuning fork on what reusing a politically charged building looks like in a rural context. Calvin says it best in this passage; “I’m more about asset-based community development…[w]e already have all the assets that we need; we just need to use them.”

Go read it, and support the Pike School of Art’s work by donating some money towards the redevelopment of the youth jail.

Hay Bale-isms

Some of you might know that I’m a big fan of hay bales. They’re cute, they’re strange, they’re good, and they’re bad. The Walker Art Center asked me to write about my train of thought for their online magazine, so here’s a piece called “Hay Bale-isms: Settler Nostalgia and the Agricultural Dreamscape”. Read it here.

The Alan Olsen 35mm Slide Collection: Photos From the RTC

Johanna Armstrong from The Fergus Falls Daily Journal wrote up a very nice piece about the Alan Olsen 35mm slide collection I’ve been scanning. Thanks Johanna! Read it here.

Scene Report: The Pet Casket Factory

I went to the pet casket factory on a whim. I read that they give tours if you call ahead, so I did. My guide breezily led me across the small factory floor, pointing out every step of the plastic molding process in detail. He didn’t ask me why I wanted a tour. I didn’t know either.

“We make nice, mid-range pet caskets. Some people want something nice, but don’t want to spend $500 or $1000 on one. Some people prefer the $80 or $100 option.”

“They say our pet caskets degrade in 100 years, but I don’t know. We’ve been in business for about 58 years, a couple have been dug up for various reasons. They were all fine."

“We make caskets as small as 10 inches, for hamsters and whatnot. We also make ones up to 58 inches, for Great Danes."

“Business is fine. We have some competition, and more and more people are opting for cremation. But we also manufacture urns. So we do okay.”

“All of our bedding is sewn by two people right here in town. Our cardboard boxes are made locally too, which we use for shipments.”

“When we grind down the plastic edges of our caskets to make them smooth, we save all the plastic particles. We get a discount from our plastic supplier when we recycle. They pay us per pound of plastic dust. So we don’t waste anything.”

My guide runs his hand through the dust, which sits in a bag, which sits in a box. The small, crumbly, beige particles stick to his fingers.

After I sign the guest book, they encourage me to take a pen with the company name on it. They also had rulers and bumper stickers. I take several. It’s all free, and slightly silly. The receptionist laughs along with me. “You seem to have a good sense of humor,” I say to her.

“In this business,” she replies, looking over her glasses, “you have to.”

Small Town Museum Round-Up, Visionary Folk Art of Wisconsin Edition: The Museum of Woodcarving

Small town museums have a kind of life cycle. Especially if they’re the product of one person’s particular vision. Their cause is a noble one. They start slowly and accumulate over time. They might relocate once or twice. They hum along in glorious obscurity. And some locals never go in, no matter how bizarre or one-of-a-kind it is.

And when a small town museum isn’t open for Memorial day, you can probably assume the owner’s died.

I had driven all the way to Spooner to see the Museum of Woodcarving, even though I didn’t know much about it. I had found it on the internet, and it looked like it was some kind of religious shrine. I thought it was worth a look. But when I got there, it was closed. Nobody in town seemed to know why - everybody just speculated.

I heard she went to Florida and never came back, a librarian told me. No, she went to Florida all right, like she always does, a bartender explained. She just got sick when she did get back.

Well, I heard she’s in a home in Hayward, a woman at a second hand store suggested. Either way, that museum she ran for her husband’s uncle? That place hasn’t been open for a year.

Before I drove back to Duluth, I left my phone number with a few different people, stuck a note on the front door, and hoped for the best.

And a few days later, it worked. A woman gave me a phone call and invited me to drive back down to see the museum, while her and a few friends cleaned out the lobby. The museum is in receivership, she explained. The owner isn’t well. I’m in charge of clearing out the building and figuring out what’s junk and what’s not.

I’m no folk art scholar, but I know a visionary artist environment when I see one. The vibe was pretty straightforward - it just felt like a 1950’s high school shop teacher was told by God to reconstruct the most medieval parts of the bible in a pole barn with a dropped ceiling and carpet.

But not a benevolent or kind God. More of a medieval, mythic, malevolent God. The same God that spoke to Hieronymus Bosch. Very old testament. A little sick.

Anyhow, the man who carved everything, Joe Barta, died a long time ago. His nephew took care of it for a long time, then when he passed on, his wife took it over. Now that she’s too sick to care for it, nobody’s left in the line of succession. Like all of our stuff, it eventually gets put up to auction, and sold to whoever shows up first.

The receiver, a woman named Bonnie, was very nice to me and let me take as many pictures as I wanted. And while she doesn’t really know how to appraise the artwork she’s stumbled into, she knows it’s not junk. She wants to find somebody to purchase the whole collection in one big lot, before she has to part it out and sell the building. She’s worried about this coming winter, when they’ll be left in the building without heat. All that freezing and thawing doesn’t do good things to your looks, not matter how blessed you are.

Note the puddle of Christ’s tears (reflecting air freshener and power outlet). Hand is broken at the wrist, for reasons unknown. The red carved wooden sign reads “On the way to his crucifixion Jesus stumbles with the cross”.

The definite centerpiece of the museum is the crucifixion. It’s held behind a velvet rope, and is almost a ready-made album cover for a metal band.

From “Carved by Prayer”, pamphlet found in the lobby of the museum.

So, I guess you could buy the whole thing. Maybe somebody reading this knows a person or a foundation who would want to buy and care for it all. Most likely, though, it’ll all be parted out, and sold to whoever gets to their favorite piece first.

It’ll be sad to see it auctioned off to punks from the cities and weirdos from the backwoods, who all drive to Spooner to get a piece of the action. Some of the sculptures will no doubt be kept indoors, in good condition, while some will probably be used in nativity scenes on the lawn of a church. Some of the devils might be used as halloween decorations in somebody’s yard. Propped up on the side of the road by a fireworks stand. Some will be varnished, shellacked, sandblasted, or even embellished with paint. They’ll start to get sunbleached and weather-beaten. They’ll become birdhouses. They’ll sink back into the ground that grew the trees that birthed them.

Maybe, as they rot, Joe Barta will be looking down from heaven, aghast at our ignorance. He’ll turn to God, who’s standing behind him. I tried to show them, he’ll say.

God will rest his hand on his shoulder and comfort him. My plan is a lot weirder than you think, Joe.

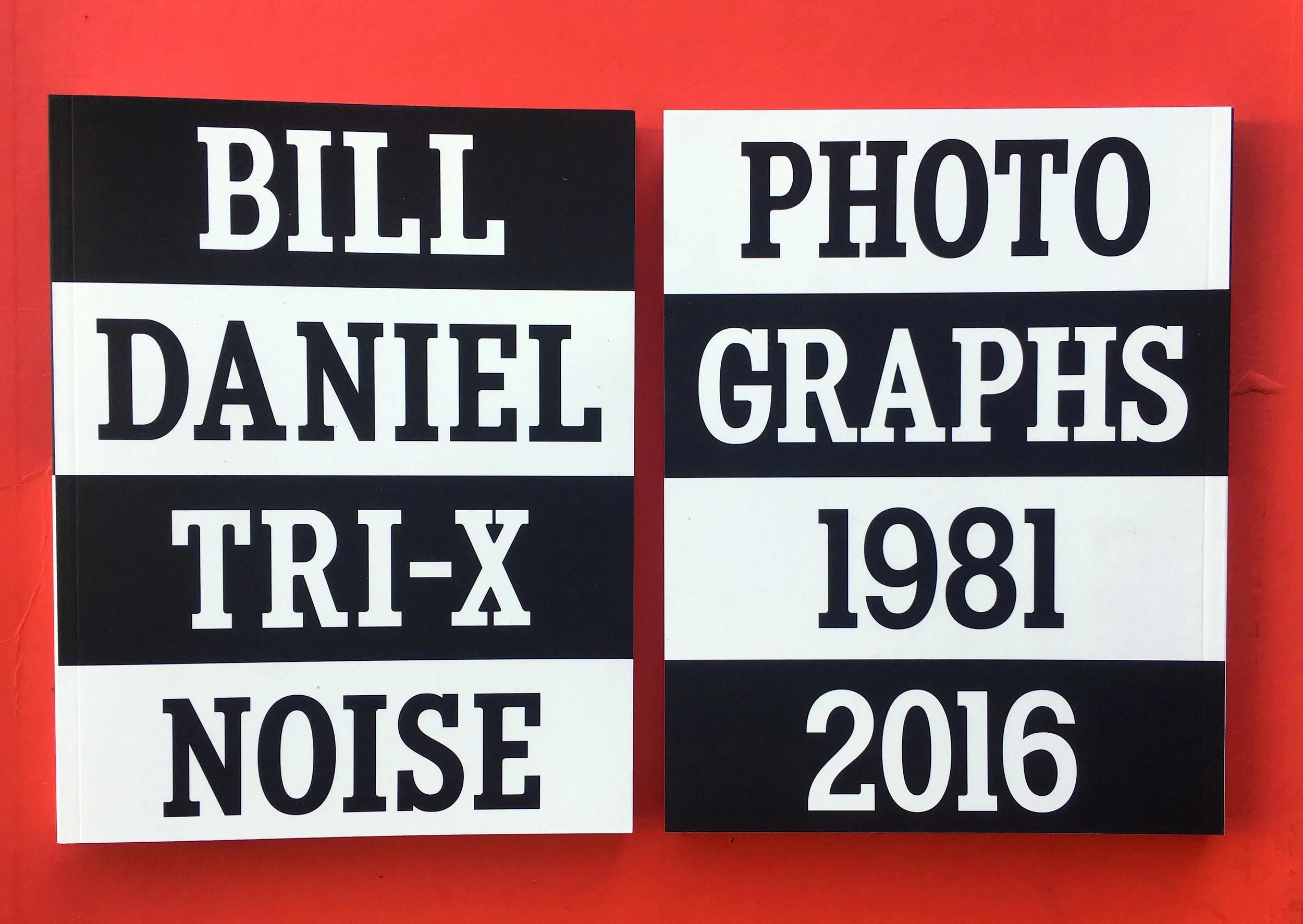

Bill Daniel's "Tri-X Noise", reviewed

The first time I stumbled over Bill Daniel’s work, I was 19 years old, on my first solo young-punk walkabout, and desperately in search of something I couldn’t quite name. I stopped into Quimby’s Bookstore in Chicago, where I bought a copy of Bill Daniel’s hobo-graffiti manual Mostly True and copy of his legendary film Who is Bozo Texino?. Mostly True was exactly the type of low weirdness I craved - part investigation, part whimsical speculative history, part seedy how-to manual, all mischievously collaged together. It was an antidote to the self-assigned self-serious punk attitude that seemed pervasive at the time.

The film, Who is Bozo Texino?, should be assigned viewing for all young aspiring documentary filmmakers - it was partially responsible for leading me to study documentary filmmaking at Evergreen. It was my entry point into avant-garde film. Bozo daisy-chained my young sponge of a mind to the films of Vanessa Renwick, Agnes Varda, Robert Berliner, Guy Maddin, Bill Brown, Barbara Hammer, Robert Flaherty, and Craig Baldwin (more on him later), and many many more. It led me to Canyon Cinema, Light Cone, and Anthology Film Archives. It set a lot of things in motion. I owe a lot to that film, and a lot to Bill because of it.

It’s a joy, then, to revisit Bill’s work with his newest book Tri-X Noise: Photographs 1981-2016 (published by Radio Raheem Records). Bill, although being well-known for Bozo, has an expansive still-image based art practice that preceded and goes beyond his moving-image opus. Tri-X Noise has clearly been a long time coming. It’s a remarkable collection of black-and-white photos that he calls a “sprawling visual journal of a life lived on the road and after dark,“ and a “flash-lit scrapbook of an invisible vanguard”; skateboarding, performance art, punk bands, and motley experiments in off-the-grid living fill its chiaroscuro pages. And yes, there’s lots of hobo monikers to soak up! Given my own entry point into Bill’s work, and my own evolution between still and moving imaged-based practices, decoding Tri-X Noise has been a blast.

Image from Microcosm Publishing.

The book is a high quality vessel, with lots to offer the discerning reader. Bill shoots 35mm black and white Kodak Tri-X film, with an off-camera flash (held with the left hand, it looks like), with a “traditional” field of view (a 28mm or so lens, a popular focal length for traditional “documentary” or “street” photography). This gives his images a remarkable consistency through the years, and it ties them together in a way that they otherwise may not be. The images have no captions; a straightforward index of descriptions is in the back of the book, along with a short bio of Bill. This method of putting descriptions in the back, rather than alongside the image in question, really lets me enjoy the images for what they are, rather than reading the text and quickly glossing over the image with my eyes. It also saves the logic of the book’s sequencing for the end; the images start in the early 1980s, when Bill was photographing skaters and bands like The Big Boys, Butthole Surfers, and Bad Brains. It then slowly creeps up to the 2010’s, featuring bands like Black Rainbow, projects like Oakland’s Black Hole Cinema, and the hobo goings-on at the Black Butte Center for Railroad Culture, taking plenty of detours along the way.

The dot that connects me to Bill is a San Franciscan one - infamous found footage maestro Craig Baldwin, who I apprenticed under, literally under Artist’s Television Access, years after Bill did a similar apprenticeship himself. This is my favorite detour: on page 72, Bill shows Craig in 1990, editing a film at a subterranean work bench, and on page 75, he appears 16 years later. Showing such a compression of time in the book, with Craig appearing as a younger man and as the gray-mopped deity I recognize him as, gives me an appreciation of the other time-travels I may just need to look closer to find. Because of Craig, I start to see and recognize San Franciscans from years past, either through their graffiti, their names in the index, or their hazy B+W mugs themselves. Bill’s perspective is an insider-outsider; while intimate and palling around with the people in front of the lens, Bill is nonetheless a “tourist in one’s own home”, to use Lucy Lippard’s phrase. He sees the meta-narrative; the historic value of documenting a scene while you’re in it and it’s still thriving.

One of Bill’s strengths as a photographer is getting close to his subjects. It sounds small, but makes a big difference. He doesn’t seem to worry about the distinction between candid or posed photos - he shoots as any of us photograph our own friends.

Only Bill and his closest friends can identify every single person and project within the pages, but as somebody a step or two removed from lots of the people appearing, it’s really nice to look deeply and find associations. Sometimes fun resonances are there to decode. On page 29, for instance, he photographs a skater named Clay Towry, in Bastrop, Texas, peeking over a dirty magazine, on the edge of a pool. His shirt reads “Made in San Francisco”, foreshadowing Bill’s own migration to the West Coast. It’s fun for me, as somebody born 7 years after this photo was taken in a totally different geography and culture, to imagine how the psychic pull of San Francisco might have been irresistible to a young skater in Texas.

Part of the pleasure of Tri-X Noise is that it functions much like a family album; for those of us who have been adjacent to some of these people and places, or ones like them, it’s beautiful to see a survey made by somebody sensitive to such underground currents, and who clearly loves every minute of surfing them.

Digging on the images themselves is a joy, especially because of how well they’re printed. The book itself is matte soft-cover, with semi-matte pages. The images are elegant, with rich blacks and bright whites. Kudos to the printer, who clearly took the time to get it right. Each image is bordered by a taught black line, which help them stand sharply against the alternating white and grey pages.

My only criticism has to do with the size of the book, which is 8.5” wide by 11” tall. Since Bill’s images are almost all horizontal and 4”x6”, they’re not well served by a vertical book. The only time the vertical space is utilized is when two images are stacked on top of one another, and this only happens a handful of times. I would love to hold a horizontally printed book of Bill’s work, so that I could mull over the detail of the images more. I would love to dig on that Tri-x grain, the shadows, highlights, and greys. Bigger isn’t always better, I know; but in my opinion, too much space is used up by the matting around the photos in Tri-X Noise. But when emailing with Bill, he mentioned to me that artistic choices aren’t the only choices an artist has to make - horizontally printed books are more challenging from a merchandising and shelving point of view.

This is my marginally critical comment about Bill’s massive artistic triumph. The book is clearly a love letter to the people who helped make Bill who he is. It has a spooky visual richness that gets better each time I revisit it. Bill Daniel is still one of my favorite artists. He’s got a consistency of vision, he keeps pushing himself to try new processes (despite maintaining his methods over decades), and he works to make himself and his friends happy first. His practice is one we could all learn from.

The final image in the book, a sneakered pair of feet that seem to belong to a stagediver, ties up the sequence of images by contradicting the previously ascending chronology from early years to recent ones. It’s labeled “D. Boon, Minutemen, Twilight Room, Dallas, 8/16/84”. This is a dedication of sorts, since Dennes Boon of the Minutemen died in 1985 on Interstate 10, a Texas-California route that I’m sure Bill has driven many times. It gives the book a somewhat bittersweet send-off, saluting a leap into the void, a tribute to Boon and the poetry of a friend taken away too early.

In Al Burian’s zine Burn Collector, Al talks about sitting in his kitchen in Providence, Rhode Island, and watching the lights on the radio towers in the distance blink in near rhythm. Every now and then, two lights would briefly blink in unison and synch up, before falling out of step again. Al sits, chews, and waits for them to line up again, enjoying the tension of waiting for them to line up before watching them just as slowly fall out of sync.

Al Burian poetically compares this synchronization to the magic found in certain eras of our short lives: the right group of housemates, the perfect band, the time when everything in your town just clicked. Finding those grooves and appreciating them while we have them seems to be the challenge and the pleasure. Tri-X Noise is a how-to manual for finding that groove, made by an artist whose practice is a lesson in deep-looking and holding your friends tight.

You can buy Tri-X Noise directly from Bill Daniel’s website.

2014, editing the book in Pasadena TX studio. photo by Beau Patrick Coulon. From Bill’s website.

Shootin' the breeze with Jes Reyes

I miss the days of artist blogs. Probably because of social media, they’ve become a digital endangered species. This is one of the reasons that I really appreciate what Jes Reyes has done with her Artists I Admire series. She’s turned her website into a really active platform for letting artists (like myself) sound off on their practice, the local challenges they face, and what makes them tick. I was lucky enough to be featured a while back, so take a look.

"The Great American Think Off" Premiere!

It's finally happening! My film, "The Great American Think Off", is showing on Pioneer Public TV!

A made-for-TV version will be broadcast as part of Postcards, Pioneer's premiere locally-produced program featuring the art, history and cultural heritage of western Minnesota. The full film (all 55 minutes!) will be broadcast later in May.

I've always wanted to tell stories that reflect the real people and enlarge the common lives of my home state, so I couldn't think of a better venue for the film's debut. Postcards is at the forefront of documenting the cultural richness of this region, and it's really an honor to have this film included in their lineup this season.

It takes a community to make a film like this. None of this couldn't have happened without the help of Tricia Towey, Christer Bechtell, Carson Davis Brown, Mary Welcome, Bethany Lacktorin, Jais Gossman, Caleb Davis Wood, Kyle Ollah, Anna Simonton, Betsy Buerkle Roder, Ashley Hanson, Chris Schuelke, Patrick Moore, the production and scheduling team at Pioneer Public Television, and, of course, my parents Kent Nerburn and Louise Mengelkoch, as well as all the citizen philosophers who let me into their lives, and the great team at the New York Mills Regional Cultural Center who pulls off such an ambitious event every year. And a huge thanks to the Jerome Foundation and the Arrowhead Regional Arts Council for helping make it happen! Thank you all, so much.

TIMES: See it on Postcards this Thursday, April 11 at 7 p.m. That episode will be rebroadcast on Sunday, April 14 at 7:30 p.m. and on Monday, April 15 at 1:30 p.m. Then, the full film will be broadcast on Friday, May 31, 2019 at 11:30 a.m.

https://twitter.com/PioneerPublicTV/status/1115617112314261507?s=20

If you're not in Pioneer's broadcast region, you can see it streaming at those same times on Pioneer's website (www.pioneer.org/postcards.)

The Grand Terrace Photo League

I made a book of photos with the people who live in an apartment complex in Worthington, Minnesota, and you can buy it here.